My late colleague -the renaissance man M.H.M. Ashraff – was a talented lawyer, articulate legislator and effective minister. He was also an accomplished poet, reciting poetry or quoting from literature at the drop of a hat. But more importantly he was a deeply humane man, who genuinely shed tears for the poor, the oppressed and the downtrodden.

I first met Ashraff in 1993, just prior to the General Election, for a feast to mark a religious celebration. We would have been passing acquaintances if not for the 1994 general election, which resulted in becoming close friends and political colleagues. In fact, in Parliament our allocated seats were next to each other, we sat beside each other in cabinet, when I moved to my official residence I found that he was my neighbor, and one day when we unknowingly sat next to each other on a flight in 1996 to watch the cricket world cup in Lahore, he said: “It appears that I am doomed to sit next to you for the rest of my life.” Sadly, that was not meant to be.

I lost a friend and Sri Lanka lost a statesman. He had a vision of a peaceful, prosperous, united Sri Lanka – a Sri Lanka without violence, oppression or injustice, where all citizens could feet at home, as equal partners in the state and society. It was this vision, I believe, that led him help create the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress. He felt Muslims, particularly the Muslim farmers and fishermen of the Eastern Province did not have a voice and say in the politics of our country. His speeches in Parliament are replete with the concerns of the people of Eravur, Kalmunai, Addalachenai and his native Nintavur.

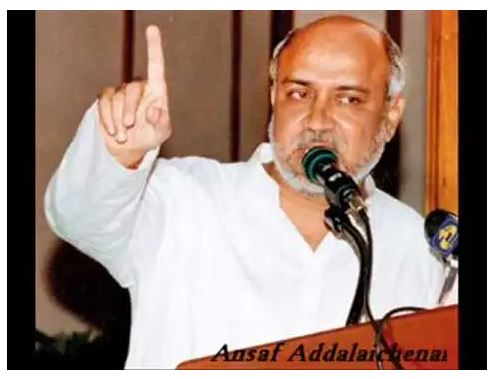

M.H.M. Ashraff

But he was not a communalist. Ashraff was deeply committed to a vision of building a just society for all Sri Lankans. Which is why for him freedom for Royal College and Ananda College was not enough. Ashraff, who over the years became fluent in English, Tamil and Sinhalese, was a man who not only fought for the freedom for Sammanthurai Maha Vidyalaya but also for Killinocchi and Weeraketiya Maha Vidyalaya. He spoke on behalf of the problems of the Tamils, the suffering of Sinhalese youth, the difficulties faced by Up-country Tamils and the issues faced by ordinary Sri Lankans. He wanted a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual and multi-religious state and society, which were shared among all Sri Lankans. In fact, just before he died, he was in the process of creating a national non-communal political party called the National Unity Alliance.

His concern for the oppressed does not mean that he endorsed the LTTE or JVP’s methods or their ideology. In fact, he was one of the LTTE’s greatest critics. But he was convinced that if Sri Lanka was to move forward, the grievances of all communities and social groups would have to be addressed. I remember him in Parliament saying once:

““So long as we allow the minorities to feel that their grievances have not been heard, that their grievances have not been remedied, then we will not be able to think as Sri Lankans and face the national crisis that we have been called upon to face.”

The challenge before us now is to make Lanka the Island of Peace. In fact, we now face the task of re-forging our constitution; as a society we are re-negotiating our contract with the state. The two main political parties have debated the national question since 1956: the time has come for a lasting solution. We cannot go on supporting or opposing a reconciliation package simply because we are in, or out, of government. But that does not mean that the final consensus will easy: it will be tough, it will take mistakes. But if we are committed to taking Sri Lanka forward, I am convinced that we can finish the task that many, including Ashraff, have laboured at before us.

It is at junctures like these that we especially miss Ashraff. He was a tough negotiator: but he was also practical, adaptable and committed to his principles. He was ever willing to engage in dialogue with all stakeholders to find creative solutions to problems as long as they fitted the principle. For example, he was steadfast in finding a configuration that would share state power in a way acceptable to all communities and actually solved the grievances of ordinary people – whether it be sharing legislative, executive, administrative or judicial power at the periphery or the centre.

The legacy Ashraff leaves us is a commitment to a just state and a compassionate society. He reminds us that we must face this country’s challenges with both our heads and our hearts. After all in him, politics was the business of poets, and poetry the business of politicians.

Sri lanka Muslims Web Portal Diversity and Inclusiveness

Sri lanka Muslims Web Portal Diversity and Inclusiveness