Arab aristocrat’s career saw him serve as an Ottoman lawmaker and the empire’s go-to man in the Hejaz region

Ottoman sovereignty over the Muslim holy city of Mecca began in 1517 after the conquest of the Mamluk Empire under Sultan Selim I, who duly took on the office of caliph.

The subsequent Turkish approach to rule in the Hejaz region, home to the Muslim holy cities, was in keeping with their style elsewhere: to allow a degree of autonomy under a local vassal who had pledged loyalty to the Ottomans.

As a result, the Sharif of Mecca remained in place as ruler of the city, continuing a dynasty that had been in place since the 10th century during Fatimid rule.

Descended from the Prophet Muhammad through his grandson Hassan, the Sharifs were members of the Banu Hashim clan and took on the name “Hashemites”.

Their position as rulers of Islam’s holiest city accorded them a prominent position within the Ottoman court as well as practical benefits such as large private armies and tax exemptions.

In the “Sharifate”, they formed an institution that remained in place until the Arab revolt against the Ottomans during the First World War.

The last man to hold the office was one Sharif Ali Haydar Pasha, who took on the task of ensuring Arab loyalty to the empire and ending the revolt led by his clansman Sharif Hussain, who had been deposed by the Turks.

His own commitment to the Turks came at a price. Within years of the Ottoman defeat in the war, the empire had collapsed, and in 1935 Ali Haydar’s life would end in exile in Lebanon, stripped of his titles and authority.

But to limit Ali Haydar’s life to its final episodes would be a disservice to a career that saw him serve as the right-hand man to the last Ottoman caliph, Abdulmecid II, and as an active parliamentarian in the Ottoman legislature.

Life in Ottoman circles

Ali Haydar was born in Istanbul in a house of his grandfather, Abdulmutallib, in 1866, and was technically a “hostage” of the Ottoman Empire to ensure the Sharifate’s loyalty to the Turks.

What that meant in reality was a silver-spooned upbringing, second only to the children of the Ottoman dynasty and not by much.

Ali Haydar Pasha was the only student at a royal school in Yildiz Palace who was not a member of the imperial family.

The result was a fraternal relationship with the royal family that saw him serve as the closest friend to the last caliph, Abdulmecid II, and also saw him groomed for a greater role in the empire by Sultan Abdulhamid II, the last Ottoman ruler who held any significant authority.

Indeed, Abdulhamid was planning to instate Ali Haydar as the emir when he reached maturity, a plan that came to an end with the caliph’s overthrow in 1909 after the Young Turk Revolution.

The Ottomans had long favoured Ali Haydar’s clan within the Sharif dynasty, with Ali Haydar belonging to the Zawi Zayd branch, and Sharif Hussain, who later led the Arab revolt, belonging to the Awn branch.

For centuries, it has been the Zayd branch that ruled over Mecca, but in the 1830s a former Ottoman vassal and ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, went to war against the Sultan, installing his preferred Sharif from the Awn branch.

The Awn had therefore become a symbol of rebellion against the Ottoman authorities, and Istanbul was keen to restore the prominence of its favoured branch.

They did this by elevating members of the Zayd clan, with Ali Haydar the foremost beneficiary, taking up a position as a cabinet minister within the Ministry of Endowments, and later joining parliament after the overthrow of Abdulhamid in 1908.

Blessed with the dual fortune that came with being an Ottoman courtesan and descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, Ali Haydar lived a life full of material trappings.

He had two mansions, one on each side of Istanbul, servants, chauffeurs and private tutors for his children and was a point man for foreign Muslim dignitaries from as far away as India.

The fight against Arab nationalists

This life of prestige would come to a premature end, however, when the First World War broke out.

The conflict gave the burgeoning Arab separatist movement the momentum it needed to finally breakaway from the Ottomans, much to Ali Haydar’s disappointment.

Writing about the Arab nationalists in his diary in early 1914, he wrote: “Their pride and self-glorification made it look as though the whole Islamic world would crash, with no one strong enough to save it.”

When the war started, with the Ottomans on the German axis side against the western allies, Ali Haydar’s main priority became to maintain unity between the Ottoman Empire’s Arabs and Turks.

The aristocrat opposed Istanbul’s suppression of the Arab nationalist cause, including the hanging of separatist leaders in Damascus in 1916.

He even went so far as to lobby the Ottomans to make concessions to their Arab subjects, such as handing over administration to locals in Arab-majority regions, making Arabic a language of primary education and increasing Arab representation in the Ottoman parliament and bureaucracy.

Even though these requests were well received by the Ottomans, the damage was done, with the empire on the back foot across is Arab territories, meaning such reforms could not be implemented.

They were further impeded by the more pressing problem of the Arab Revolt, which began in 1916 when Sharif Hussain entered into an alliance with the British.

Hussain was offered recognition as king of the Hejaz, so long as he helped expel the Ottomans from Arab lands. That moved Ali Haydar to action, as he believed the future of the Arabs lay under Ottoman rule.

“The prosperity of Arabia could only be assured if that country remained in the orbit of an enlightened Ottoman Empire,” he wrote, adding that the last thing he wanted was “to see Arabia severed from the Turkish connection as the result of warfare”.

In a statement addressing Arab tribes, who were supporting the revolt, Ali Haydar said: “Do not attempt to break away from the Ottoman Empire when the general condition of the world is in a state of upheaval.”

‘Do not attempt to break away from the Ottoman Empire when the general condition of the world is in a state of upheaval’

– Ali Haydar Pasha, last Ottoman Sharif of Mecca

He further asked: “Why should we shed so much Muslim blood on either side?”

In June 1916, Sharif Hussain was dismissed from his position as Sharif of Mecca and Ali Haydar took his place.

Following a simple ceremony, he left for the Hejaz to help the Ottoman army tackle the rebellion.

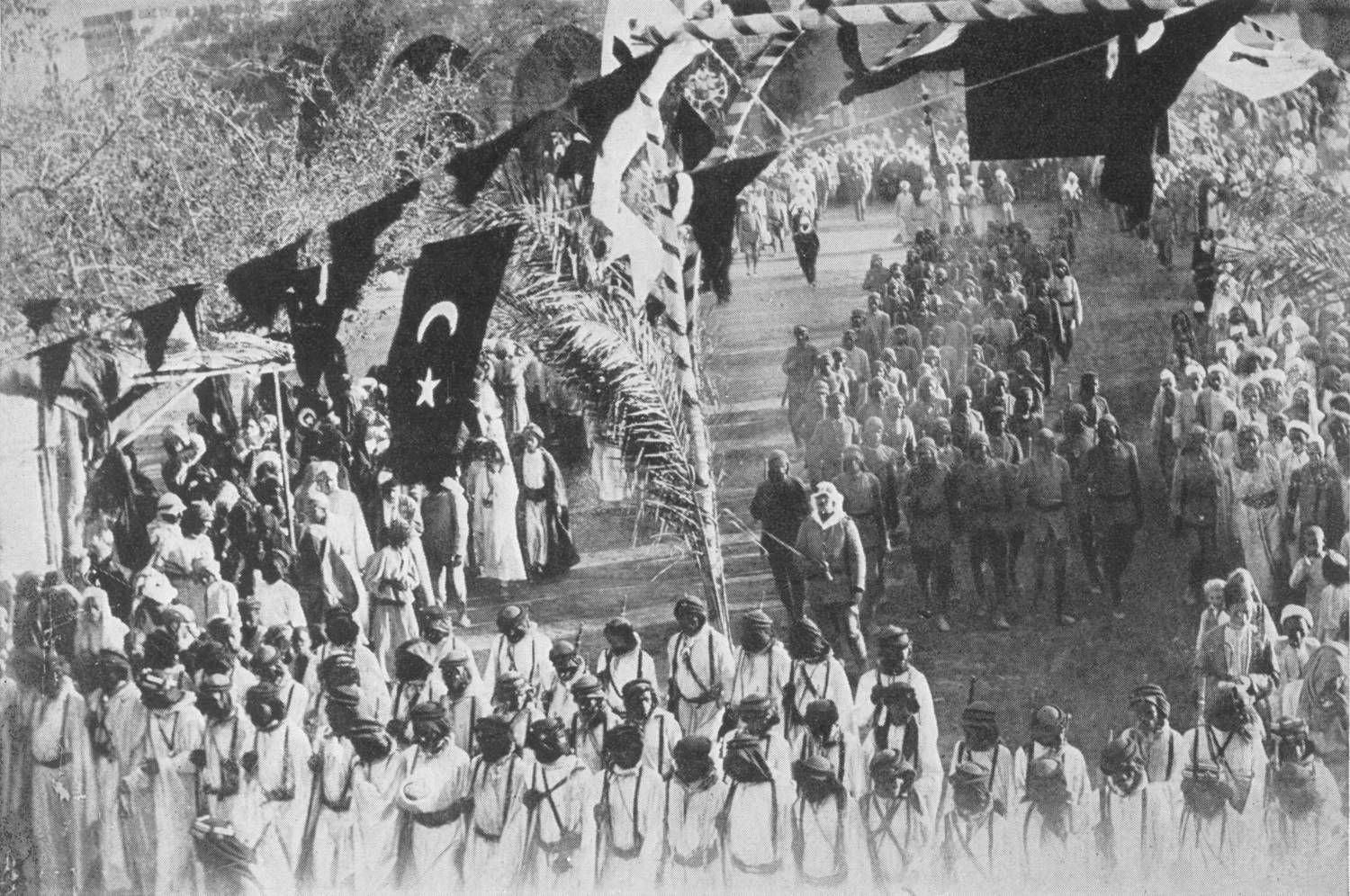

When he arrived in Medina, 15,000 armed Arabs were waiting for him, ready to take on the British-backed rebellion.

In the months that followed, he rushed from one front to another, trying to convince Arab tribes not to join the rebellion and instead remain loyal to the Turks.

It was an effort that proved futile with the eventual Ottoman defeat and subsequent occupation of northern Arab lands by British and French forces.

Things fared little better for Sharif Hussain, whose kingdom in the Hejaz succumbed to Saudi forces in the mid-1920s, paving the way for the creation of the Saudi state.

The Turkish Republic, exile and death

In 1918, Ali Haydar Pasha returned to Istanbul, which was under British occupation following the Ottoman defeat.

Surveying the city while travelling in a ferry towards his mansion in Istanbul’s Camlica Hill district, Pasha wrote: “I appealed to God to allow this beautiful country to remain in the hands of the Muslims.”

His wish would be fulfilled but not quite in the way the staunch Ottoman loyalist would have wanted.

Turkish troops under Mustafa Kemal, later Ataturk, launched their “national struggle” to free the Turkish mainland from European occupation, and by 1923 most of that vision had been accomplished, including the liberation of Istanbul.

Ali Haydar sent a cable to Ataturk congratulating him on his military successes in Anatolia, but the joy would be tinged with the sorrow of what was to come.

In 1922, the Ottoman Empire ceased to exist and by 1924 the caliphate was also abolished.

As a devout Muslim, Ali Haydar was against adopting any western cultural codes, but the newly formed republic moved to limit the role of Islam in public life. That included the adoption of western-style dress, as well as the closure of Islamic schools and Sufi lodges.

Members of the royal family were exiled, including Ali Haydar’s own son, Abdulmecid, who had married Sultan Murad V’s granddaughter, Rukiye Sultan.

Refusing to wear western style hats as stipulated by the Republican government, Ali Haydar preferred to remain indoors at home, and, with his courtly stipends ended, was forced to sell his horses, car and other luxuries.

“It was with mingled feelings that I said goodbye to my home for the last time,” he wrote in his diary after he finally decided to leave his birthplace of Turkey.

“When we sailed, I could not bear to see the last of my beloved Istanbul, but I gazed toward the hill of Uskudar and thought of my family at Camlica,” he continued.

The last Emir of Mecca, Ali Haydar Pasha died in 1935 in Beirut in extreme poverty with no income, no authority and little esteem.

Things fared better for his children, with Abdulmecid later serving as Jordan‘s ambassador to Turkey, and others becoming businessmen, artists and novelists.

Ali Haydar Pasha’s diary was in Turkish but was translated into English by his second wife, Fatma, formerly Isabel Dunn, the daughter of a British officer serving in Istanbul.

The text was sent to George Stitt, a British soldier who had become Ali Haydar’s friend during Istanbul’s occupation. He published the diary in 1948 in London with the title of A Prince of Arabia: The Emir Shereef Ali Haider.

Post Disclaimer | Support Us

Support Us

The sailanmuslim.com web site entirely supported by individual donors and well wishers. If you regularly visit this site and wish to show your appreciation, or if you wish to see further development of sailanmuslim.com, please donate us

IMPORTANT : All content hosted on sailanmuslim.com is solely for non-commercial purposes and with the permission of original copyright holders. Any other use of the hosted content, such as for financial gain, requires express approval from the copyright owners.

Sri lanka Muslims Web Portal Diversity and Inclusiveness – Sri Lanka Muslims

Sri lanka Muslims Web Portal Diversity and Inclusiveness – Sri Lanka Muslims

This is a must read for all those interested in Islamic history and the Ottoman Khilafat. It shows that there were a good number of noble Sharif families who actually supported the Ottoman Turks against the inroads of Western Imperialism.