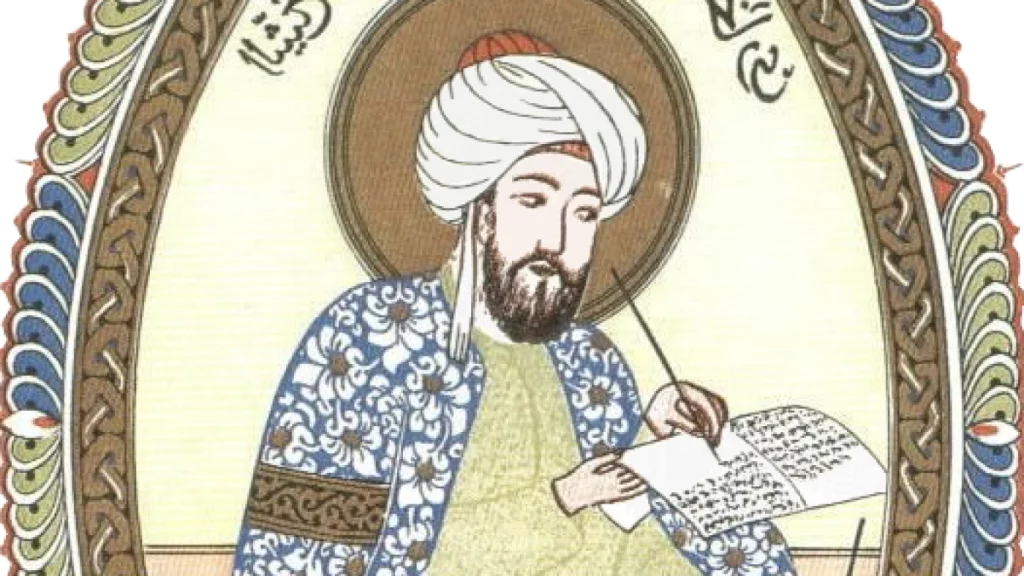

Born in 980 CE to a Persian family near the city of Bukhara in modern day Uzbekistan, Abu Ali al-Hussain ibn Abdullah al-Balkhi would go on to become one of the greatest minds of his era, profoundly influencing future scholarship in fields as diverse as medicine, philosophy and astronomy.

Known as Ibn Sina in the Islamic world and Avicenna among western scholars, the polymath is synonymous with the period in Islamic history that is widely and controversially referred to as the “Islamic Golden Age”.

The Persian scholar’s work had a far-reaching impact both in the Islamic world and later in Europe, with critiques and defences of his theories continuing into the modern era.

So great was Ibn Sina’s impact, particularly on the European imagination, that he – alongside the Andalusian philosopher Ibn Rushd (Averroes) and the famed Muslim warrior Saladin – appears among the “virtuous pagans” in Dante’s Inferno, occupying the first circles of hell alongside other non-Christians, such as Plato, Socrates and Virgil.

He is also credited with preserving and building upon the ideas of the Greek philosopher Aristotle, whose ideas form the bedrock of the modern scientific method.

For Islamic revivalists, Ibn Sina is an example of the intellectual flourishing that occurred during the early centuries of Islam, and serves to rebuke the idea that the religion is an impediment to scientific and philosophical thought.

Who was Ibn Sina?

Ibn Sina was born in the 10th century in the village of Afshana, which like much of Central Asia at the time was ruled by the Samanid Empire, a Sunni Muslim state of Iranian origin.

The period was marked by the breakdown in the Baghdad-based Abbasid Caliphate’s central authority and the rise of independent Muslim entities.

Despite this relative political instability, the intellectually friendly atmosphere that the Abbasids had fostered in the Islamic world endured, with scholarship heavily entwined with the study of religion. It was in this context that Ibn Sina was raised by a father who had adopted the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam.

While the young Ibn Sina did not follow in his father’s religious footsteps, choosing the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam, it is likely that debates with the Ismailis were formative in his intellectual development, both religious and secular.

Speaking of his interactions with the Ismailis in his autobiography, Ibn Sina writes: “I would listen to them and comprehend what they were saying but my soul would not accept it… and they began to summon me to it with constant talk on their tongues about philosophy, geometry, and Indian arithmetic.”

Typical of other Islamic intellectuals of the period, Ibn Sina’s education was a mix of religious and secular subjects, such as mathematics, medicine and philosophy. By the age of 10 he had memorised the Quran, and by his mid-teens he had earned a reputation as a physician.

A devout Muslim, the young Ibn Sina dedicated a significant amount of time to the study of Islamic texts and Greek philosophy, seeking to marry the two by proving the existence of God using logic and reason, rather than blind faith.

By the age of 32, the scholar was appointed vizier of the Buyid state after treating its emir, Shams al-Dawla. Once the monarch died, Ibn Sina declined an offer made by his son and successor to continue in the role.

What was he famous for?

As a physician, one of Ibn Sina’s most notable contributions was his book Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine), an encyclopedia which oscillates between medical knowledge gained from the ancients and more contemporary findings by Islamic scientists.

The book was translated into Latin during the 12th century, and from there it was used as a reference text throughout European universities until the mid-17th century.

As well as describing 600 potential cures for common illnesses, Ibn Sina also described the anatomy of body parts, such as the eye and the heart. A skilled botanist, he also mentions the effect plants and roots had on the human body.

A key medical contribution was his work on the effect of quarantines on limiting the spread of illness, arguing that a 40-day period of self-isolation was essential in order to stop infections from affecting others.

Outside of medicine, his important works included The Book of Healing, which was split into four sections and covered an array of subjects, such as mathematics, metaphysics, natural sciences and logic.

His scientific works included arguments that light had a specific speed, descriptions of how sound travelled through air, a theory on motion and psychological works on the relationship between mind, body and the ability to perceive.

In a form of pre-modern psychiatry, the physician also described how mental ailments, such as depression and anxiety, had an impact on the body.

Others fields of interest included natural phenomena, such as earthquakes and cloud formation. With regard to the former, the polymath said tremors were a result of the movement of land and activity underneath the Earth.

As an astronomer, Ibn Sina observed the planet Venus against the disc of the sun and was able to conclude that the planet was closer to the Earth than to the sun. He also found that the SN 1006 supernova, which was observable for three months at the turn of the first millennium CE, was temporarily the brightest object in the sky, outshining Venus and observable even during daylight.

The scientist is also credited with inventing a device to monitor the coordinates of stars and for determining that stars were self-luminous.

What was his philosophy?

In philosophy, Ibn Sina’s main contribution was the development of his own form of Aristotelian logic and the use of rationality and reason to establish the existence of God.

His works on logic featured within nine books that are part of The Book of Healing, and in these he argued for the utility of logic, and pointed out perceived errors in earlier works on the topic. He wrote that logic is crucial in determining the validity of arguments and the development of knowledge, and that the aim of logic was to establish truth.

While critiquing his Greek predecessor Aristotle, the Persian polymath likewise believed that humans had three types of soul: the vegetative, animal and rational psyches. The first two bind humans to Earth, and the rational psyche connects people to God.

On the existence of God, Ibn Sina published Burhan al-Siddiqin (Proof of the Truthful), in which he lay out an argument for the “necessary existent” or something that cannot not exist. He explained that everything outside of this necessary existent is contingent on the existence of something else, which is its cause. So, for example, a person’s own existence is contingent on the existence of their parents, whose existence is in turn contingent on the existence of their parents, and so on.

When the aggregate of all contingent things in existence is considered, Ibn Sina determined that the sum remains contingent, as in it requires a non-contingent cause outside of itself, which he identified as God.

The reasoning was later criticised by Ibn Rushd for relying on metaphysics rather than demonstrable laws of nature.

What did he say about human senses?

One of Ibn Sina’s life goals was to accurately understand the human senses and to demonstrate that there was more to them than was understood by his contemporaries. He proposed that we all have inner senses which complement our outer, widely acknowledged, senses, such as sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch.

A strong believer in intuition, Ibn Sina believed that common sense was an internal sense and attributed some of the soul’s functions to this. The act of forming and making a judgment can, therefore, be understood as an act of the soul in his world view.

Retentive imagination was another internal sense allowing humans to remember the information they gathered through common sense. This internal sense stores the form of things in our mind, enabling people to reference that information and recognise the things around them.

Compositive animal imagination is a sense, which Ibn Sina said allows animals to learn what they should avoid or seek out in their natural surroundings. Similarly, compositive human imagination allows humans to learn what we should seek and avoid around us.

The ability to make judgments about surroundings was called estimative power by Ibn Sina, who said that it allows us to determine what is dangerous or beneficial for us – for example, having a fear of something.

Finally, Ibn Sina stated that our memory was responsible for storing all the information developed by our other senses, and that processing was the ability to use all of the information to the highest of our internal senses’ abilities.

Ibn Sina died in June 1037, at 58 years old after suffering from a long battle with colic. He was buried in Hamdan, Iran where his tomb has been converted into a mausoleum.

The museum holds an extensive collection of artefacts, including coins and pottery which date back to the first millennium BC, as well as a library containing thousands of books. One of the most iconic features of the mausoleum is the spindle-shaped tower inspired by the spindle-shaped tower of the Ziyarid-era Kavus Tower.

Today, Ibn Sina’s work is still widely commemorated. In Ankara, Turkey, the Ibn Sina University Hospital is named after him. Beyond science, Ibn Sina’s influences extended to the field of music, literature and nature.

Post Disclaimer | Support Us

Support Us

The sailanmuslim.com web site entirely supported by individual donors and well wishers. If you regularly visit this site and wish to show your appreciation, or if you wish to see further development of sailanmuslim.com, please donate us

IMPORTANT : All content hosted on sailanmuslim.com is solely for non-commercial purposes and with the permission of original copyright holders. Any other use of the hosted content, such as for financial gain, requires express approval from the copyright owners.

Sri lanka Muslims Web Portal Sri Lanka Muslims News Center

Sri lanka Muslims Web Portal Sri Lanka Muslims News Center

Donate

Donate